For this second post in Zed Decoded, our blog & video series in which we're taking a closer look at how Zed is built, I've talked to Zed's three co-founders — Nathan, Max, Antonio — about the data structure at the heart of Zed: the rope.

Companion Video

Rope & SumTree

This post comes with a 1hr companion video, in which Thorsten, Nathan, Antonio, and Max use Zed to look at how Zed uses the Rope and SumTree types. It's a loose conversation in which we write and read a lot of code to understand how the rope in Zed works and is implemented.

Going in I knew that data structures to represent text are a favorite topic in text editor circles. I had also used the Rope type in the Zed codebase and knew a little bit about ropes.

What I didn't really understand was how Zed's rope is implemented and what that implementation enables. So I asked Nathan, Max, and Antonio about it. They've been writing code on top, below and inside the rope for years now. And, as it turns out, Zed's rope isn't really a rope, at least not in the classical sense. It's very impressive, but first: what's a rope?

Why not a string?

One of the most important things a text editor has to do is to represent text in memory. When you open a file in a text editor, you expect to see its contents and want to navigate through it, and — hey, that's where the name comes from — you also want to edit the text.

To do that, a text editor has to load the file contents into memory — you can't just let the user stare at the raw bytes on disk. You also want to keep it in memory, because not every change should immediately be saved to disk.

So the question is: how do you represent the text in memory?

My naive first choice would be to use a string. Good old string. Our best friend from when we started programming. Why not use a string? It's how we represent text in memory all the time. It's not immediately obvious that that would be a bad choice, right?

Hey, I bet you could go a long way with a string, but there are some problems with strings that prevent them from being the best choice, especially once you start dealing with large files and want your program to still be efficient and responsive.

Problems with strings

Strings are usually allocated as a continuous block of memory. That can make edits inefficient. Say you have a file with 20k lines in a string and you want to insert a word right in the middle of that string. In order to do that, you have to make room for the new word in the middle of the string, so that you still end up with a string that's a continuous block of memory. And to make room, you have to move all of the text that would come after your newly inserted word. And moving here really means making allocations. In the worst case you have to move everything — all 20k lines — to make room for your new word.

Or say you want to delete a word: you can't just poke a hole in a string, because that would mean it isn't a string — a continuous block of memory — anymore. Instead you have to move all the characters except the ones you deleted, so that you end up with a single, continuous block of memory again, this time without the deleted word.

When dealing with small files and small strings, these aren't problems. We all do similar string operations all day every day, right? Yes, but most of the time we're talking about relatively small strings. When you're dealing with large files and thus large strings or a lot of edits (maybe even at the same time — hello multiple cursors!) these things — allocations, moving strings in memory — become problems.

And that's not even touching on all the other requirements a text editor might have of its text representation.

Navigation, for example. What if the user wants to jump to line 523? With a string and without any other data, you'd have to go through the string, character by character, and count the line breaks in it to find out where in the string line 523 is. And then what if the user presses the down-arrow ten times to go down ten lines and wants to end up in the same column? You'll again have to start counting line breaks in your string and then find the right offset after the last line break.

Or, say you want to draw a horizontal scrollbar at the bottom of your editor. To know how big the scroll thumb has to be, you have to know how long the longest line in the file is. Same thing again: you have to go through the string and count the lines and this time keeping track of the length of each line too.

Or what if the text file you want to load into your editor is larger than 1GB and the language you used to implement your text editor can only represent strings up to 1GB? You might say "1GB of string should be enough for everybody" but that only tells me you haven't talked to enough users of text editors yet.

Kidding aside, I think we've established that strings probably aren't the best solution to represent text in a text editor.

So what else can we use?

What's better than a string?

If you really love strings, you might now be thinking "better than a string? easy: multiple strings." And you wouldn't be that far off! Some editors do represent text as an array-of-lines with each line being a string. VS Code's Monaco editor worked that way for quite a while, but an array of strings can still be plagued by the same problems as a single string. Excessive memory consumption and performance issues made the VS Code team look for something better.

Luckily, there are better things than strings. Builders of text editors have long ago realized that strings aren't the best tool for the job and have come up with other data structures to represent text.

The most popular ones, as far as I can tell, are gap buffers, piece tables, and ropes.

They each have their pros and cons and I'm not here to compare them in detail. It's enough to know that they are all significantly better than strings and different editors made different decisions in face of different trade-offs and ended up with different data structures. To give you a taste: Emacs uses gap buffers, VS Code uses a twist on piece tables, Vim has its own tree data structure, and Helix uses a rope.

Zed, too, uses a rope. So let's take a look at the rope and see what advantages that has over a string.

Ropes

Here's how Wikipedia explains what a rope is:

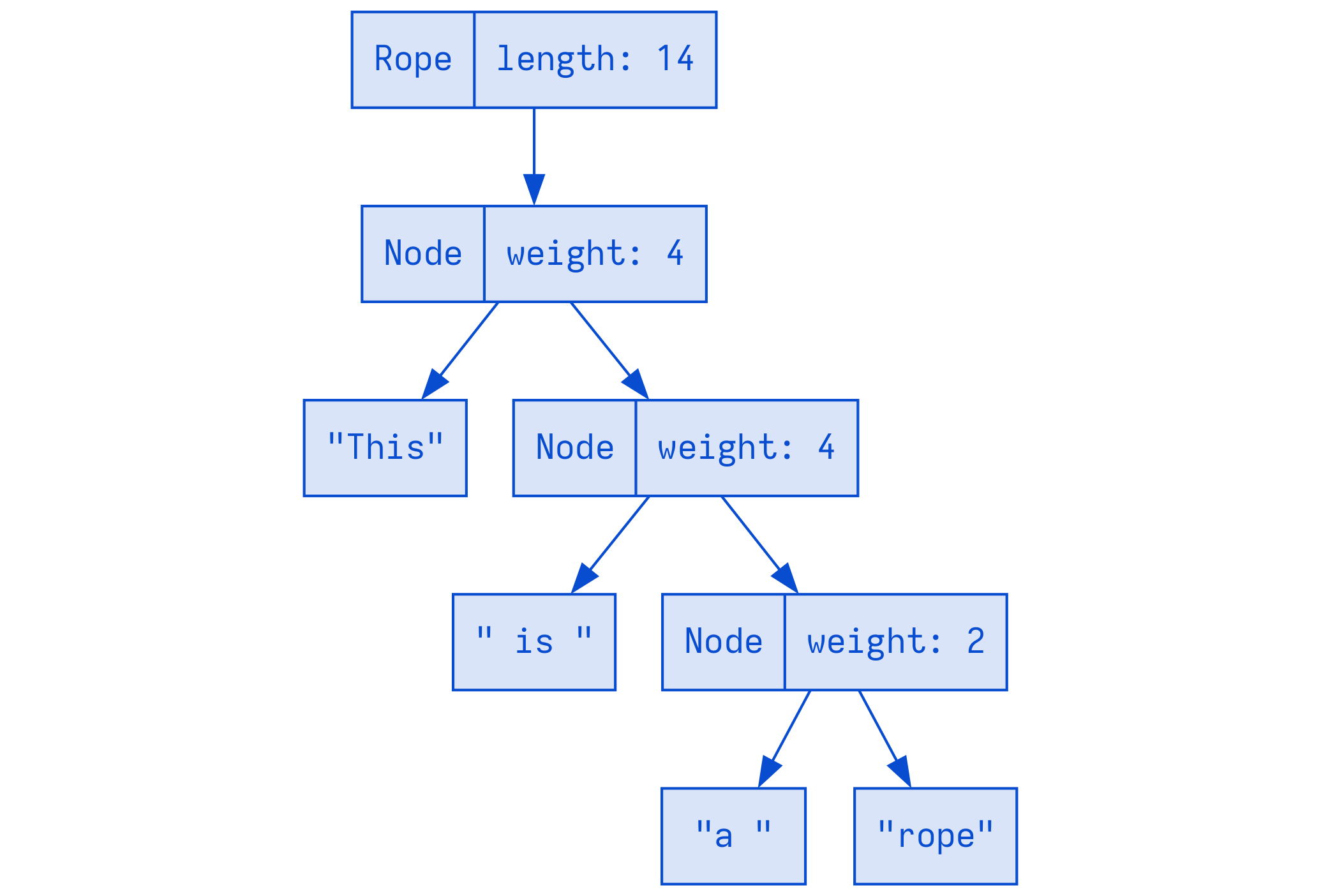

A rope is a type of binary tree where each leaf (end node) holds a string and a length (also known as a "weight"), and each node further up the tree holds the sum of the lengths of all the leaves in its left subtree.

Instead of a continuous block of memory, a rope is a tree and its leaves are the characters of the text it represents.

Here's what the text "This is a rope" would look like in a rope:

You might now be thinking that this is a lot more complex than a string and you'd be right — it is. But here's the crucial bit that makes this a rope triumph over strings in many cases: the leaves - "This", " is ", "a ", "rope" — are essentially immutable. Instead of modifying strings, you modify the tree. Instead of poking holes in strings and moving parts of it around it memory, you modify the tree to get a new string. And by now, we as programmers have figured out how to efficiently work with trees.

Let's use the example from above again: deleting a word at a certain position in the text. With a string, you'd have to reallocate all of the text that comes after the word, possibly the whole string. With a rope, you find the start and end positions of the word you want to delete, then split the tree at these two positions so you have four trees, you throw away the middle two trees (that only contain the deleted word), concatenate the other two, then rebalance the tree. Yes, it does sound like a lot and it does require some algorithmic finesse under the hood, but the memory and performance improvements over strings are very real: instead of moving things around in memory, you only have to update a few pointers. That might look silly for a text as short as "This is a rope", but it pays off big time when you have very large texts.

I understand that this is very abstract, so let me show you. Let's take a look at Zed's rope implementation.

Zed's rope implementation

Zed has its own rope implementation in its own crate: rope. (One reason for why Zed has its own implementation instead of using a library is that a lot of libraries didn't exist when the Zed founders laid the groundwork for Zed in 2017.)

The main type in the rope crate is Rope. Here's how you'd use it:

let mut rope = Rope::new();

rope.push("Hello World! This is your captain speaking.");So far, so similar to String. Now let's say we have two ropes:

let mut rope1 = Rope::new();

rope1.push("Hello World!");

let mut rope2 = Rope::new();

rope2.push("This is your captain speaking.");If we want to concatenate them, all we have to do is this:

rope1.append(rope2);

assert_eq!(

rope1.text(),

"Hello World! This is your captain speaking.".to_string()

);The call to rope1.append connects the two trees — rope1 and rope2 — by building a new tree that contains both. That's barely more than updating a few pointers. Compare that to strings: if you concatenate two strings, you'll have to move at least one of them in memory so that they end up next to each, forming a continuous block. Often you have to move both of them, because there's not enough space after the first string. Again: the text in this example is laughably short, but what if someone wants to have ten copies of the 25k line SQLite amalgamation in a single file?

What about replacing a word?

// Construct a rope

let mut rope = Rope::new();

rope.push("One coffee, please. Black, yes.");

// Replace characters 4 to 10 (0-indexed) with "guinness".

rope.replace(4..10, "guinness");

assert_eq!(rope.text(), "One guinness, please. Black, yes.");What happens under the hood:

replace()creates a new rope that contains all of the nodes of the originalrope, up until the 5th character (c)- the new text,

guinness, is appended to the new rope - the rest of the original

rope, everything after character 11, is appended to the new rope

Deleting a word? Just replace it with "":

let mut rope = Rope::new();

rope.push("One coffee, please. Black, yes.");

rope.replace(4..10, "");These operations are very quick even when dealing with large amounts of text, because then most of the nodes in the tree can be reused and only have to be rewired.

But what happens with the word that was deleted, "coffee"? The leaf nodes that contain these characters will get automatically cleaned up as soon as no other node references them anymore. That's what immutable leaf nodes in ropes enable: when a rope is mutated, or a new rope is constructed from an old one, or two ropes are merged into a new one, essentially all that's changing are references to leaf nodes. And those references are counted: as soon as there's no reference to a node anymore, the node gets cleaned up, deallocated.

To be precise and get technical: the leaf nodes, the ones containing the actual text, aren't fully immutable in Zed's rope implementation. These leaf nodes have a maximum length and if, say, text gets appended to a rope and the new text is short enough to fit into the last leaf node without exceeding its maximum length, then that leaf node will be mutated and the text appended to it.

On a conceptual level, though, you can think of the rope as a persistent data structure and its nodes as reference-counted immutable nodes in a tree. That's what makes it a better choice than the string and brings us back to the question we skipped above: why did Zed chose a rope instead of one of the other data structures?

Why use a rope in Zed?

Zed's goal is to be a high-performance code editor. Strings, as we saw, won't get you to high-performance. So what do you use instead? Gap buffers, ropes, piece tables?

There isn't a single, obvious best choice here. It all comes down to specific requirements and trade-offs you're willing to make to meet those requirements.

Maybe you've heard that gap buffers can be faster than ropes, or that they're easier to understand, or that piece tables are more elegant. That may be true, yes, but that still doesn't mean they're an obvious choice over, for example, a rope. Here's what the author of ropey, a popular rope implementation in Rust, wrote about the performance trade-offs between ropes and gap buffers:

Ropes make a different performance trade-off, being a sort of "jack of all trades". They're not amazing at anything, but they're always solidly good with

O(log N)performance. They're not the best choice for an editor that only supports local editing patterns, since they leave a lot of performance on the table compared to gap buffers in that case (again, even for huge documents). But for an editor that encourages non-localized edits, or just wants flexibility in that regard, they're a great choice because they always have good performance, whereas gap buffers degrade poorly with unfavorable editing patterns.

Ropes are "not amazing at anything, but they're always solidly good." It depends on what you want to do, or what you want your editor to be able to do.

So what if you really want to make use of all the cores in your CPU? In "Text showdown: Gap Buffers vs Ropes" concurrency is mentioned in a paragraph at the end:

Ropes have other benefits besides good performance. Both Crop and Ropey [note: both are rope implementations in Rust] support concurrent access from multiple threads. This lets you take snapshots to do asynchronous saves, backups, or multi-user edits. This isn't something you could easily do with a gap buffer.

In the companion video you can hear what Max said about this paragraph: "Yeah, it matters more than any of that other stuff." Nathan added that "we use that all over the place", with "that" being concurrent access, snapshots, multi-user edits, asynchronous operations.

In other words: concurrent access to the text in a buffer was a hard requirement for Zed and that's why the rope ended up being the top choice.

Here's an example of how deeply ingrained concurrent access to text is into Zed: when you edit a buffer in Zed, with syntax highlighting enabled, a snapshot of the buffer's text content is sent to a background thread in which it's re-parsed using Tree-sitter. That happens on every edit and it's very, very fast and efficient, since the snapshots don't require a full copy of the text. All that's needed is to bump a reference count, because the reference-counting for the nodes in Zed's rope is implemented with Arc, Rust's "thread-safe reference-counting pointer".

That brings us to the most important bit: how Zed's rope is implemented. Because it isn't implemented like the classic rope you see on Wikipedia and its implementation gives Zed's rope certain properties that other rope implementations might not have and that implementation is actually what put the rope ahead of other data structures.

It's not a rope, it's a SumTree

Zed's rope is not a classic binary-tree rope, it's a SumTree. If you open up the definition of Zed's Rope, you'll see that it's nothing more than a SumTree of Chunks:

struct Rope {

chunks: SumTree<Chunk>,

}

struct Chunk(ArrayString<{ 2 * CHUNK_BASE }>);A Chunk is an ArrayString, which comes from the arrayvec crate and allows storing strings inline and not on the heap somewhere else. Meaning: a Chunk is a collection of characters. Chunks are the leaves in the SumTree and contain at most 2 * CHUNK_BASE characters. In release builds of Zed, CHUNK_BASE is 64.

So then what is a SumTree? Ask Nathan and he'll say that the SumTree is "the soul of Zed". But a slightly more technical description of a SumTree is this:

A SumTree<T> is a B+ tree in which each leaf node contains multiple items of type T and a Summary for each Item. Internal nodes contain a Summary of the items in its subtree.

And here are the type definitions to match, which you can find in the sum_tree crate:

struct SumTree<T: Item>(pub Arc<Node<T>>);

enum Node<T: Item> {

Internal {

height: u8,

summary: T::Summary,

child_summaries: ArrayVec<T::Summary, { 2 * TREE_BASE }>,

child_trees: ArrayVec<SumTree<T>, { 2 * TREE_BASE }>,

},

Leaf {

summary: T::Summary,

items: ArrayVec<T, { 2 * TREE_BASE }>,

item_summaries: ArrayVec<T::Summary, { 2 * TREE_BASE }>,

},

}

trait Item: Clone {

type Summary: Summary;

fn summary(&self) -> Self::Summary;

}So what's a Summary? Anything you want! The only requirement is that you need to be able to add multiple summaries together, to create a sum of summaries:

trait Summary: Default + Clone + fmt::Debug {

type Context;

fn add_summary(&mut self, summary: &Self, cx: &Self::Context);

}But I know you just rolled your eyes at that, so let's make it more concrete.

Since the Rope is a SumTree and each item in the SumTree has to have a summary, here's the Summary that's associated with each node in Zed's Rope:

struct TextSummary {

/// Length in UTF-8

len: usize,

/// Length in UTF-16 code units

len_utf16: OffsetUtf16,

/// A point representing the number of lines and the length of the last line

lines: Point,

/// How many `char`s are in the first line

first_line_chars: u32,

/// How many `char`s are in the last line

last_line_chars: u32,

/// How many UTF-16 code units are in the last line

last_line_len_utf16: u32,

/// The row idx of the longest row

longest_row: u32,

/// How many `char`s are in the longest row

longest_row_chars: u32,

}All nodes in the SumTree — internal and leaf nodes — have such a summary, containing information about its subtree. The leaf nodes have a summary of their Chunks and the internal nodes have a summary that is the sum of the summaries of its child nodes, recursively down the tree.

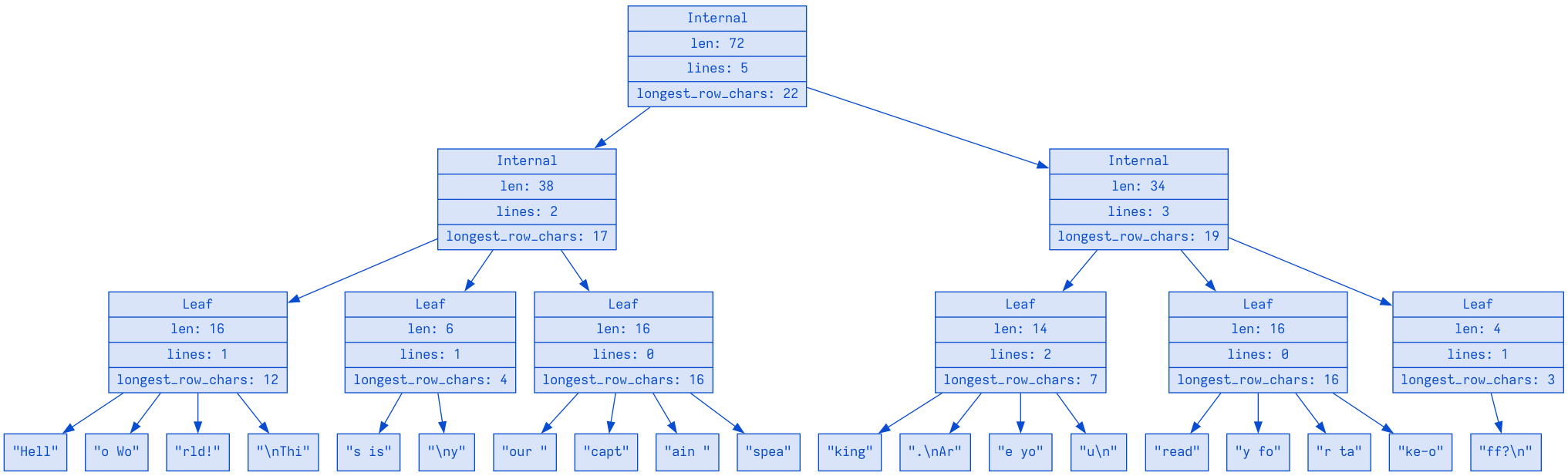

Let's say we have the following text:

Hello World!

This is

your captain speaking.

Are you

ready for take-off?

5 lines of text. If this is pushed into a Zed Rope, the SumTree beneath the Rope would look like this, simplified:

(I left out some of the fields of TextSummary to keep the diagram small-ish and also adjusted the maximum size of the chunks and maximum number of children per node. In a release-build of Zed, all five lines of the text would fit in a single node.)

Even with only three summary fields — len, lines, longest_row_chars — we can see that the summaries of the internal nodes are the sum of their child nodes summaries.

The root node's summary tells us about the complete text, the complete Rope: 72 characters, 5 lines, and the longest line has 22 characters (your captain speaking.\n). The internal nodes tell is about parts of the text. The left internal node here tells us, for example, that it's 38 characters from "Hell" to "spea" (including newline characters) and that there are two line breaks in that part of the text.

Okay, you might be thinking, a B+ tree with summarized summaries — what does that buy us?

Traversing a SumTree

The SumTree is a concurrency-friendly B-tree that not only gives us a persistent, copy-on-write data structure to represent text, but through its summaries it also indexes the data in the tree and allows us to traverse the tree along dimensions of the summaries in O(log n) time.

In Max's words, the SumTree is "not conceptually a map. It's more like a Vec that has these special indexing features where you can store any sequence of items you want. You decide the order and it just provides these capabilities to seek and slice."

Don't think of it as a tree that allows you to lookup values associated with keys (although it can do that), but think of it as a tree that allows you lookup items based on the summaries of each item and all the items that come before it in the tree.

Or, in other words: the items in a SumTree are ordered. Their summaries are also ordered. The SumTree allows you find any item in the tree in O(log N) time by traversing the tree from root to leaf node and deciding which node to visit based on the node's summary.

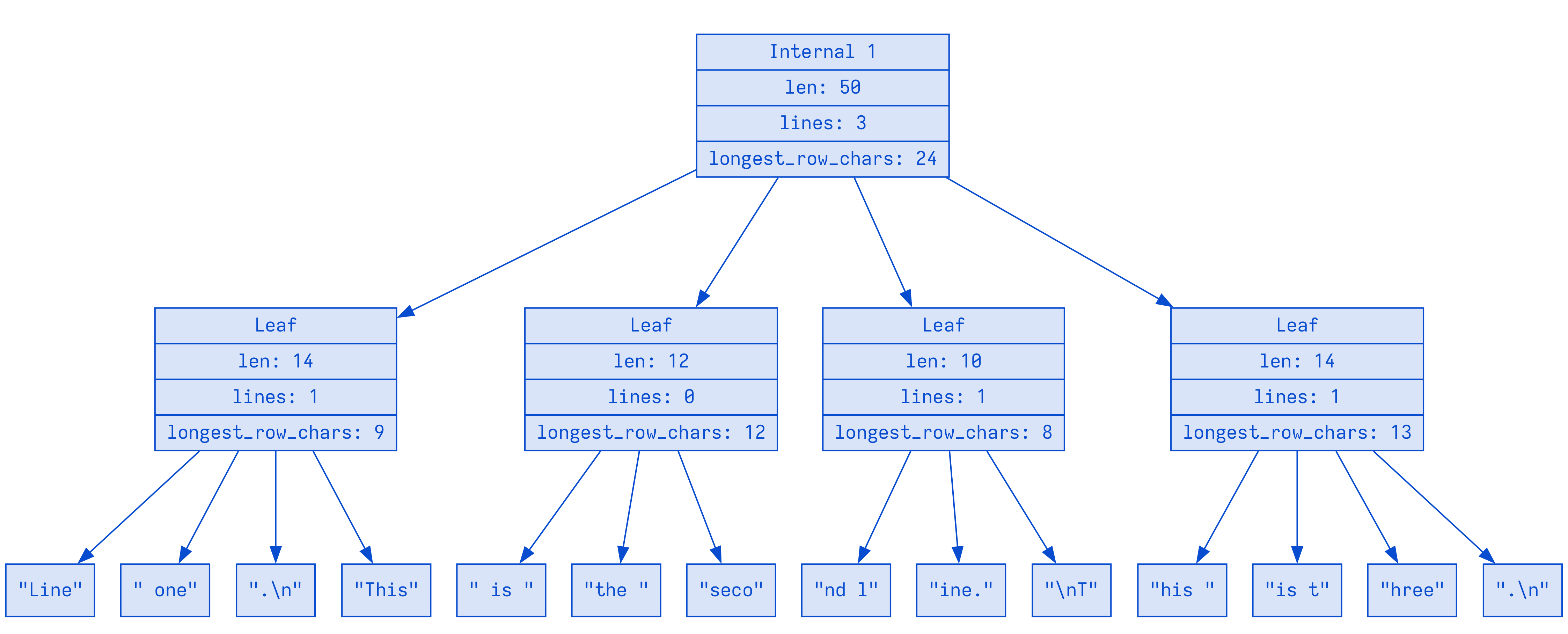

Say we have a Rope with three lines of text in it:

let mut rope = Rope::new();

rope.push("Line one.\n");

rope.push("This is the second line.\n");

rope.push("This is three.\n");Once the Rope is constructed, it looks like this:

Like we said above: each leaf node will hold multiple Chunks and each leaf node's summary will contain information about the text in its Chunks. The type of that summary is TextSummary from above. That means each node's summary can tell us about the len of the text in its chunks, the lines & rows in them, the longest line, and all the other fields of TextSummary. The internal nodes in the SumTree then contain summaries of the summaries.

And since the items in the tree — internal nodes, leaf nodes, chunks — are ordered we can traverse that tree very efficiently, because the SumTree allows us to traverse the tree based on the values in the summaries. It allows us to seek along a single dimension, a single field for example, of a given summary.

Say we want to find out what the line and column in the rope is at the absolute offset 26. Meaning: what's at character 26? In order to find out, we can traverse this three-line rope along the len field of the TextSummary. Because the len field, when added up from left to right, is an absolute offset. So in order to find what's at absolute offset 26, we traverse down the tree, taking left or right turns, depending on the len value in the summaries of the internal nodes, until we end up at the leaf node we want:

let point = rope.offset_to_point(26);

assert_eq!(point.row, 1);

assert_eq!(point.column, 16);On the surface, the call to rope.offset_to_point(26) converts an absolute 0-based offset (26) into a row and column (1 and 16). What happens inside of offset_to_point is that a cursor traverses the SumTree until it finds the items where the aggregated len of the TextSummary is >= 26. Once it found the first leaf node where that's true, it finds the exact chunk where the offset matches and parks the cursor there. On the way there, it not only kept counting the len field of the summaries it came across, but it also aggregated the lines field, which contains row and column. Neat, right?

Here's what I just described but in actual code, here's the offset_to_point method on the Rope:

fn offset_to_point(&self, offset: usize) -> Point {

if offset >= self.summary().len {

return self.summary().lines;

}

let mut cursor = self.chunks.cursor::<(usize, Point)>();

cursor.seek(&offset, Bias::Left, &());

let overshoot = offset - cursor.start().0;

cursor.start().1

+ cursor

.item()

.map_or(Point::zero(), |chunk| chunk.offset_to_point(overshoot))

}What it does is the following:

- sanity checks that the offset isn't past the end of the whole

Rope - creates a cursor that seeks along the

usize(offset) andPoint(aPointis a struct with two fields:rowandcolumn) dimensions, aggregating both while doing that - once it found an item at

offset, it calculates the overshoot: theoffsetwe're looking for might be in the middle of a single chunk andcursor.start().0is theusize(offset) at the start of a given chunk - take the lines up to the start of the current chunk (

cursor.start().1) — which is the summary ofTextSummary.lenof the complete tree to the left of the current item! - add them to the lines at the offset in the, possibly, middle of the chunk (

chunk.offset_to_point(overshoot))

The most interesting bit here is, of course, the cursor that's constructed with self.chunks.cursor::<(usize, Point)>(). This particular cursor has two dimensions and allows you to seek to a value on one dimension (usize) in the given SumTree and in the same operation also get the sum of the second dimension, the Point, at a particular cursor position.

The beauty of that is that it can do that in O(log N) time, because each internal node contains a summary of summaries (meaning: the total len of all items in its subtree in this case) and it can skip over all of those where len < 26. In the diagram above, you can see that we don't even have to traverse the first two leaf nodes.

Isn't that amazing? There's more.

Using the SumTree

You can also traverse the SumTree the other way around, seeking along lines/rows and getting the final offset:

// Go from offset to point:

let point = rope.offset_to_point(55);

assert_eq!(point.row, 2);

assert_eq!(point.column, 6);

// Go from point to offset:

let offset = rope.point_to_offset(Point::new(2, 6));

assert_eq!(offset, 55);And — you probably guessed it — point_to_offset looks exactly like offset_to_point, except that the dimensions with which the cursor is constructed are flipped:

fn point_to_offset(&self, point: Point) -> usize {

if point >= self.summary().lines {

return self.summary().len;

}

let mut cursor = self.chunks.cursor::<(Point, usize)>();

cursor.seek(&point, Bias::Left, &());

let overshoot = point - cursor.start().0;

cursor.start().1

+ cursor

.item()

.map_or(0, |chunk| chunk.point_to_offset(overshoot))

}This seeking along one dimension and aggregating (summarizing!) along multiple dimensions is made possible by some very clever Rust code that I won't explain in detail, but the short version is this.

Given a TextSummary like the following (which we already saw in full above) and a ChunkSummary that wraps it...

struct TextSummary {

len: usize,

lines: Point,

// [...]

}

struct ChunkSummary {

text: TextSummary,

}... we can define the len and lines fields as sum_tree::Dimensions:

impl<'a> sum_tree::Dimension<'a, ChunkSummary> for usize {

fn add_summary(&mut self, summary: &'a ChunkSummary, _: &()) {

*self += summary.text.len;

}

}

impl<'a> sum_tree::Dimension<'a, ChunkSummary> for Point {

fn add_summary(&mut self, summary: &'a ChunkSummary, _: &()) {

*self += summary.text.lines;

}

}With that we can then construct cursors for a given sum_tree::Dimension or a tuple of dimensions (which is what we did above with (usize, Point)).

Once constructed, the cursor can then seek along any Dimension we have defined and aggregate either the complete TextSummary or just a single Dimension of a given summary type.

Or we can also seek along a single dimension and then get the whole summary once the cursor has found the target:

let mut rope = Rope::new();

rope.push("This is the first line.\n");

rope.push("This is the second line.\n");

rope.push("This is the third line.\n");

// Construct cursor:

let mut cursor = rope.cursor(0);

// Seek it to offset 55 and get the `TextSummary` at that offset:

let summary = cursor.summary::<TextSummary>(55);

assert_eq!(summary.len, 55);

assert_eq!(summary.lines, Point::new(2, 6));

assert_eq!(summary.longest_row_chars, 24);The cursor stopped in the middle of line 2, at column 6, and up until that location the longest_row_chars in the summaries was 24.

This is very, very powerful stuff. To scratch the surface: it allows us to easily convert between UTF8 rows/columns and UTF16 rows/columns, which is sometimes required when working with the language server protocol (LSP). Just seek to a UTF8 Point and aggregate the UTF16 Points:

fn point_to_point_utf16(&self, point: Point) -> PointUtf16 {

if point >= self.summary().lines {

return self.summary().lines_utf16();

}

let mut cursor = self.chunks.cursor::<(Point, PointUtf16)>();

cursor.seek(&point, Bias::Left, &());

// ... you know the rest ...

}But there's more and I could go on and on and on and show more examples or use big words like monoid homomorphism, but I'll stop here. You get the idea — the SumTree, a thread-safe, snapshot-friendly, copy-on-write B+ tree is very powerful and can be used for more than "just" text, which is why it's everywhere in Zed. Yes, literally.

Everything's a SumTree

Currently there are over 20 uses of the SumTree in Zed. The SumTree is not only used as the basis for the Rope, but in many different places. The list of files in a project is a SumTree. The information returned by git blame is stored in a SumTree. Messages in the chat channel: SumTree. Diagnostics: SumTree.

At the very core of Zed sits a data structured called DisplayMap that contains all the information about how a given buffer of text should be displayed — where the folds go, which lines wrap, where the inlay hints are displayed, ... — and it looks like this:

struct DisplayMap {

/// The buffer that we are displaying.

buffer: Model<MultiBuffer>,

/// Decides where the [`Inlay`]s should be displayed.

inlay_map: InlayMap,

/// Decides where the fold indicators should be and tracks parts of a source file that are currently folded.

fold_map: FoldMap,

/// Keeps track of hard tabs in a buffer.

tab_map: TabMap,

/// Handles soft wrapping.

wrap_map: Model<WrapMap>,

/// Tracks custom blocks such as diagnostics that should be displayed within buffer.

block_map: BlockMap,

/// Regions of text that should be highlighted.

text_highlights: TextHighlights,

/// Regions of inlays that should be highlighted.

inlay_highlights: InlayHighlights,

// [...]

}Guess what? All of these use a SumTree under the hood and in a future post we will explore them, but the point I want to make now is this:

The Zed co-founders didn't so much decide to use a rope over a gap buffer or over a piece table. They started with the SumTree, recognized how powerful it is, how it fits Zed's requirements, and then built the rope on top of it.

The rope may be at the heart of Zed, but the SumTree is, to quote Nathan again, "the soul of Zed".

Related Posts

Check out similar blogs from the Zed team.

Looking for a better editor?

You can try Zed today on macOS, Windows, or Linux. Download now!

We are hiring!

If you're passionate about the topics we cover on our blog, please consider joining our team to help us ship the future of software development.