This fall, we shipped a new Settings Editor in Zed. On the surface, it looks like something every editor has: a window with categories on the left and controls on the right. You open it, tweak a few preferences, and get back to your code. Under the hood, building that "simple" window forced us to rethink how settings are modeled across the entire codebase, and to teach our UI framework, GPUI, a few new tricks. This post is a look at the design and implementation work that went into it.

So much complexity

Settings are particularly important for a code editor like Zed. We spend so much of our time in one, and small annoyances can add up quickly. Further, settings are deeply intertwined with our projects. We have settings per project, settings on servers, and user settings (just to name a few). With the settings editor, we wanted to make it easy to discover and manage all of these settings in a unified interface.

Before the new Settings Editor, the only way to interact with Zed's vast set of knobs was through the settings.json file.

Despite trying to make this file as friendly as possible, it's impossible to make new settings discoverable with a simple JSON file.

Distributed settings and runtime registration

Before the refactoring, Zed's settings were defined in a distributed way: each crate in the codebase declared the settings it needed, and the app stitched them together at runtime to interpret the single JSON file. This kept compile times manageable, but it meant there was no unified, strongly-typed model of all settings. Definitions were scattered, so it was hard to trace where a setting lived or to make changes without unintended side effects (spoiler: we would learn this the hard way).

The macro approach (and why it didn't stick)

In our first pass at building the Settings Editor, we tried to build on top of the then current architecture instead of rethinking it. Our initial idea was to use a macro: you'd declare a setting in Rust, annotate it with some UI metadata, and the macro would generate the code needed to wire it into the Settings Editor.

We hoped that we could lean on Rust's type system, get a nice UI, and avoid touching the underlying architecture too much. But in practice, this collided with the structure of our crate graph.

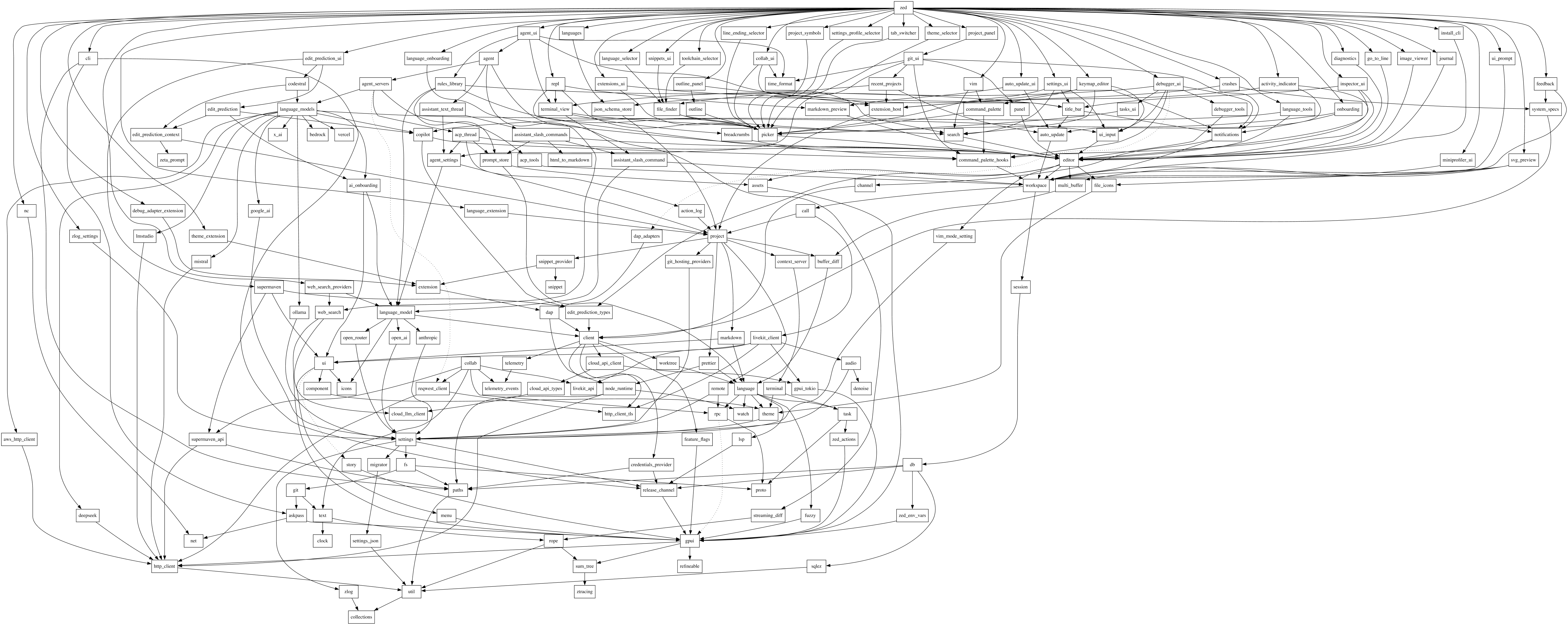

If you draw out Zed's crates, you see two big regions:

- A "pre-UI" region where we read files, talk to the network, and manage core data structures

- A "UI" region where all the components live: dropdowns, pickers, buttons, etc

Some settings naturally belonged in the "pre-UI" core region. Others belonged in the UI region. The problem was that gluing UI concerns into non-UI crates (or vice versa) via macros and shared data structures turned into a tangle. We tried to smooth that over by adding intermediate types:

- One layer to describe the settings from the code

- Another layer to describe the UI

- Another to bridge them together

It still didn't feel solid. Each layer added complexity without really solving the underlying problem, which was that the settings model itself wasn't well-structured.

When architecture bites back: the auto-update bug

We were also using this project as a chance to clean up some long‑standing quirks in how settings behaved—for example, clarifying the difference between a setting that's simply unset and one that's intentionally set to "nothing." Those distinctions matter when deciding whether a value can be reset or how multiple layers of configuration should merge.

In the middle of making these adjustments within the old distributed architecture, we accidentally broke auto‑updating: the app couldn't update itself, and users had to manually install the next version. It was a clear sign that too many pieces were interacting in ways that weren't obvious, and that we needed a simpler, more centralized model.

Centralizing settings as strong types

The simplification was straightforward: instead of scattering settings definitions across many crates, we consolidated them into a single location and expressed them as clear, strongly typed structures that map directly to configuration files.

In practice, this meant introducing two core types: UserSettings, which represents a user's global configuration, and ProjectSettings, which captures per-project overrides.

With these in place, the old patchwork of values gathered from throughout the codebase gave way to a small, coherent model. Parsing and validation became simpler, the Settings Editor gained a single authoritative source to work from, and changes became far easier to reason about. That foundation also set up the next big question: how should these settings files shape the UI itself?

Files as the organizing principle

We'd been treating the existence of the settings files as "just" storage, an implementation detail of how settings are managed. But as we reconsidered our approach, it became clear that the file is actually the organizing principle, both for the UI and for the code.

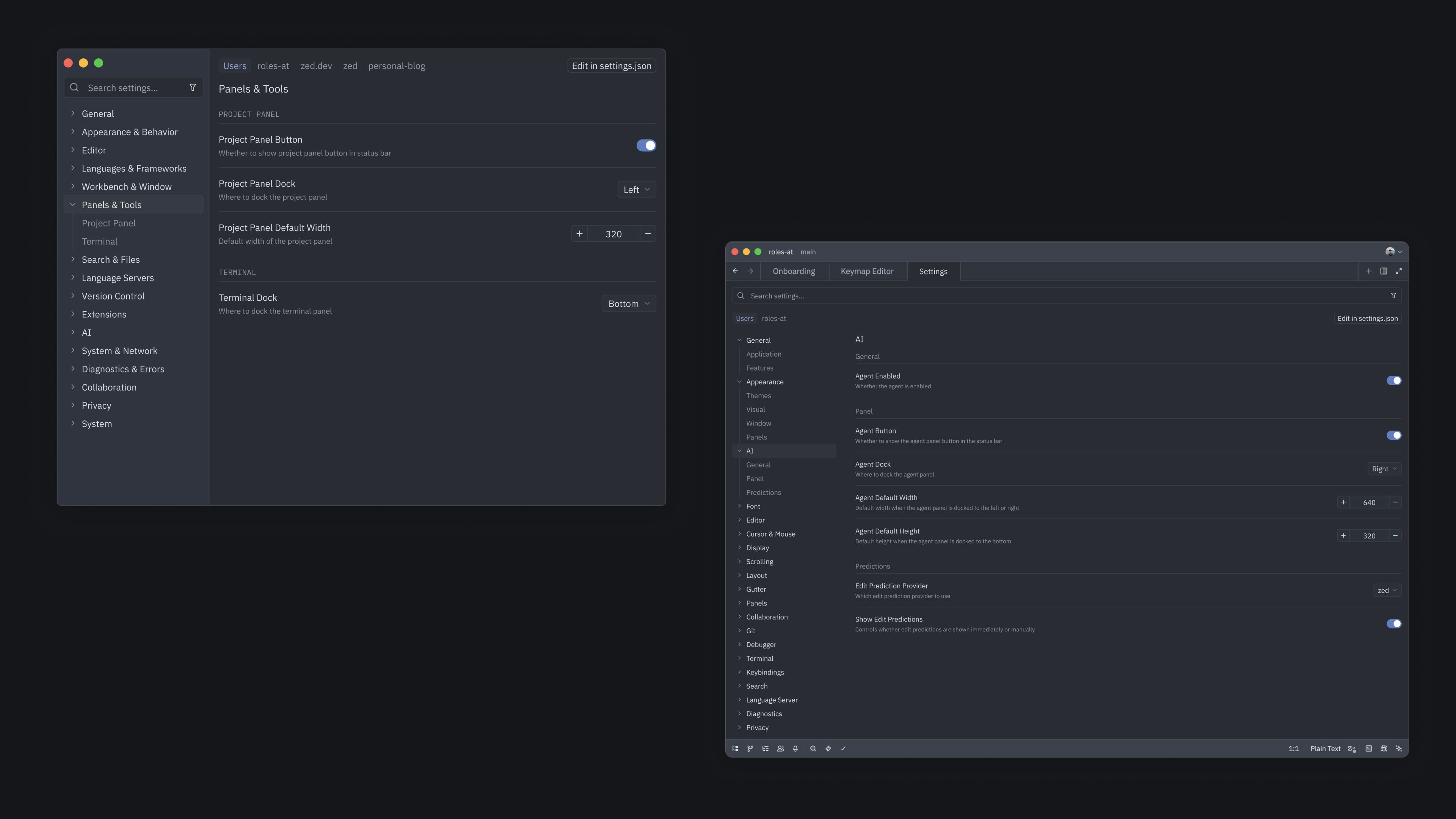

On the UI side, we were initially split between two patterns: a separate window like in most native apps vs. a tab like in many web based applications (like VS Code). We had prototypes for both approaches and both had their advocates on our team.

We couldn't decide between the two approaches until we considered how the settings file should be represented in each UI. The main Zed workspace window is conceptually "focused" on your project: a specific codebase, a specific set of files. But the settings files have their own sense of location. User settings apply to everything, project settings interact with those user settings but apply to their own subset of files. If we treated the Settings Editor as "just another tab" in the workspace, we were mixing those concepts of location: the main workspace window would be about your project, except when it suddenly wasn't in the settings tab.

Even though this might happen in other areas of Zed today, putting the Settings Editor in its own window let it operate in a separate conceptual space with its own sense of "focus", that might not even be related to your current project.

The implementation mirrored this separation.

UserSettings and ProjectSettings became distinct, clearly scoped types, and the UI could work directly from them rather than pulling information from scattered definitions.

If we had considered what a principled relationship between the settings files and the rest of the code would look like, we could have avoided the detour into the macro approach and the resulting complexity.

In both UI and code, the key move was the same: start from the files, and think deeply about how they relate to everything else. Once we did that, the design and the architecture for the Settings Editor crystallized quickly.

Building the Settings Editor in GPUI

Refactoring the settings model was only half of the story. The other half was building some UI automation into GPUI, our custom UI framework, to make interacting with the Settings Editor truly smooth.

Up until recently, GPUI has been tuned for strange, custom UI elements. Terminals, code editors, and the project panel are all highly interactive custom UI elements that have their own concept of focus and state that they manage themselves.

The Settings Editor needs the opposite: a large form with structured controls, sections, and interaction patterns that users intuitively understand from the web. We had to expand what GPUI is good at. We needed better defaults for two areas in particular: focus navigation and how we organize state across many small, interactive components.

Automated focus handling and tab groups

GPUI already allows fine-grained focus management via a primitive called FocusHandle, a pointer to a location in the element tree that can then be focused or used to query the current focus state relative to the handle.

This was great for low-level control, but it would have been a lot of error prone work to use the APIs for settings UI.

We started with the web's tabindex API to allow us to mark elements that should be focusable, and that can be reached with just the tab key.

But this API is famously unusable with all values except 0 and -1.

To fix this, we introduced a new concept of tab groups: local scopes that "reset" the tab index within their region.

With these we were able to move almost all of the keyboard navigability into the UI itself without writing any additional code.

fn render_page(

&mut self,

window: &mut Window,

cx: &mut Context<SettingsWindow>,

) -> impl IntoElement {

let page_content;

v_flex()

.id("settings-ui-page")

.track_focus(&self.content_focus_handle.focus_handle(cx))

.bg(cx.theme().colors().editor_background)

.child(

div()

.flex_1()

.size_full()

.tab_group() // <- Tagging this container as a local navigable scope

.tab_index(CONTENT_GROUP_TAB_INDEX)

.child(page_content),

);

}Bringing state closer to where it's used

In Zed's core interfaces, state tends to be large and centralized: a text buffer represents the truth of the document; a project tree represents the truth of the file system.

The Settings Editor isn't like that.

It's made of many small components; dropdowns, toggles, text fields; each of which has its own relatively simple or ephemeral state. Whether each dropdown is open or closed doesn't need to be centralized for the UI to function properly.

To support this style of interaction, we expanded GPUI with an API that allows state to live directly inside the UI tree.

It behaves a little like React's useState hook, but designed for our engine's update model:

struct MyComponent;

impl RenderOnce for MyComponent {

fn render(self, window: &mut Window, cx: &mut App) {

let state: Entity<String> = window.use_state(cx, |_, _| "initial value");

// ...

}Learn more in the "Ownership and data flow in GPUI" blog post.

This shift reduced the amount of boilerplate needed to glue everything together, and it made the UI easier to reason about during development.

There were some growing pains. Early versions recreated certain components more often than necessary, leading to memory leaks.

Once we addressed those issues with use_state, we encountered a few subtle bugs in how state was scoped.

Iterating on those issues helped us solidify a more ergonomic, reliable pattern for future UIs.

What this unlocks

Though the development of our Settings Editor wasn't straightforward, we hope using it feels simple!

There's more for us to do, and the settings.json file will always remain there if you want unfettered control, but we're proud of this new UI and how it helps us build more complex features.

This project left us with a much cleaner foundation. Settings are now modeled as strong, well-defined types instead of scattered registrations, and GPUI grew in important ways. All these improvements pay dividends not only for this project, but for many other future Zed features to come.

If you haven't yet explored the new Settings Editor, open it with cmd/ctrl-, the next time you're in Zed.

What looks like a simple window reflects a lot of work under the surface—and it lays the groundwork for what we can build next.

Related Posts

Check out similar blogs from the Zed team.

Looking for a better editor?

You can try Zed today on macOS, Windows, or Linux. Download now!

We are hiring!

If you're passionate about the topics we cover on our blog, please consider joining our team to help us ship the future of software development.